Who are the essential workers keeping the New Orleans region going?

Published: May 07, 2020

This brief is a profile of workers in industries deemed “essential” and where a large portion of the workforce is likely still present on site. It covers demographics, earnings, and other characteristics to spotlight a few of the overlapping vulnerabilities that workers on the frontlines of COVID-19 may face.

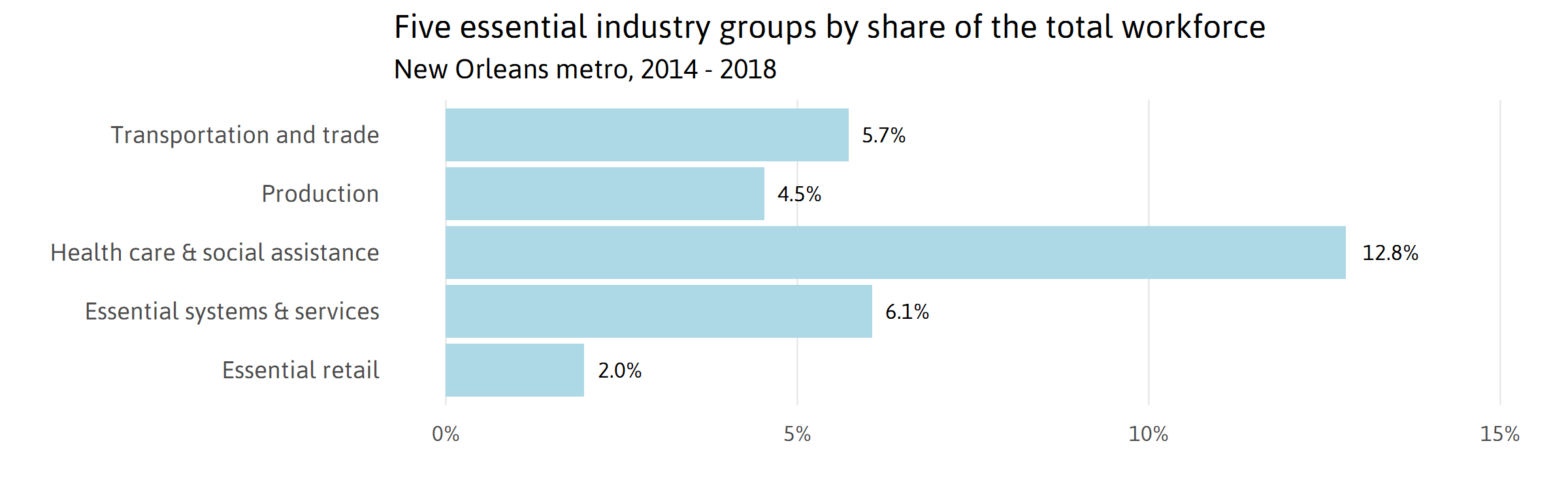

The New Orleans region could not run without the workers deemed “essential” under Louisiana’s statewide stay-at-home order, whether we are in a pandemic or not. In the 8-parish New Orleans metro, we estimate that as much as 31 percent of the workforce is employed in essential industries. These workers likely continue to go to work outside their homes—putting their health and the health of their households at higher risk of exposure to continue making a living and to maintain essential functions. This analysis looks at demographics, earnings, and family responsibilities to highlight the unequal burdens and risks faced by essential workers in the New Orleans metro.

Our profile of essential workers draws from separate national analyses by the Center for Economic and Policy Researchi and Brookingsii that took different approaches to defining essential industries. Since our list is slightly different and relatively inclusive, we grouped essential industries into the following broad categories.

- “Transportation and trade” includes transportation and logistics, wholesalers, and public transit, among others.

- “Production” includes manufacturing, oil and gas extraction, and agriculture and fishing, among others.

- “Health care & social assistance” includes hospitals and health care providers, as well as nursing and residential care and community services.

- “Essential systems and services” includes critical infrastructure, utilities, public safety, and cleaning services, among others.

- “Essential retail” includes grocery stores, convenience stores, pharmacies, and supercenters, among others.

As with similar analyses, our definition of essential workers is best treated as an approximation that likely undercounts some workers and overcounts others. For example, the restaurant and childcare industries, where some locations still have workers present on site, are excluded from the definition, although childcare workers are highlighted separately below.

Demographics and earnings

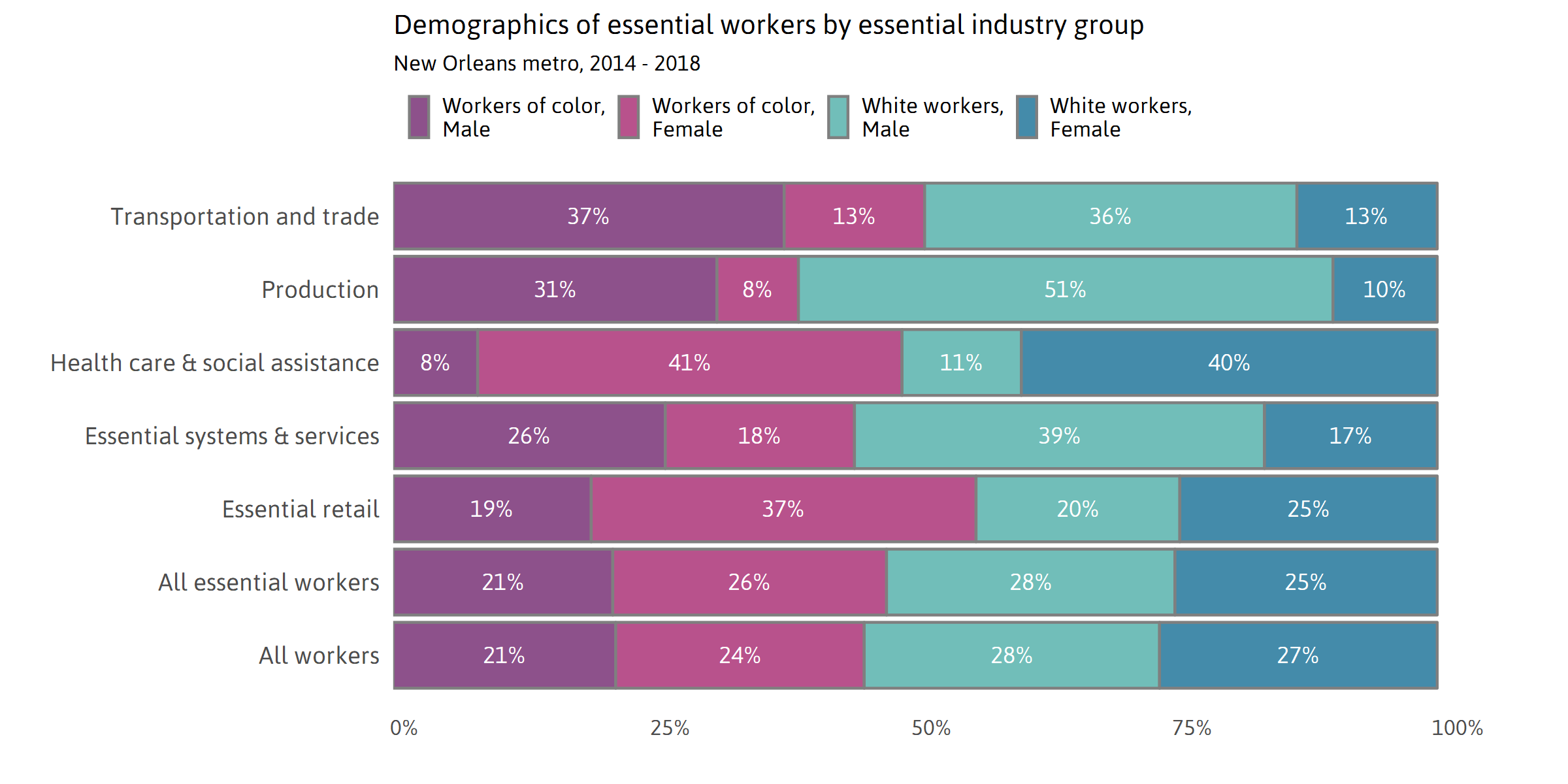

Reports on the essential workforce nationallyiii and in other citiesiv and statesv vi as well as media coveragevii have focused on the high shares of women, people of color, and low-wage workers. The broader definition used here suggests that the race and gender composition of essential workers is not too different from that of the entire metro workforce.

However, women are more likely to be employed in frontline health care and retail jobs. Women of color and white women are overrepresented in health care and social assistance, and women of color make up a disproportionate share of essential retail workers. Transportation and trade and production workers are more likely to be men. Workers of colorviii are overrepresented in essential retail (56 percent), transportation and trade (50 percent), and health care and social assistance (49 percent).

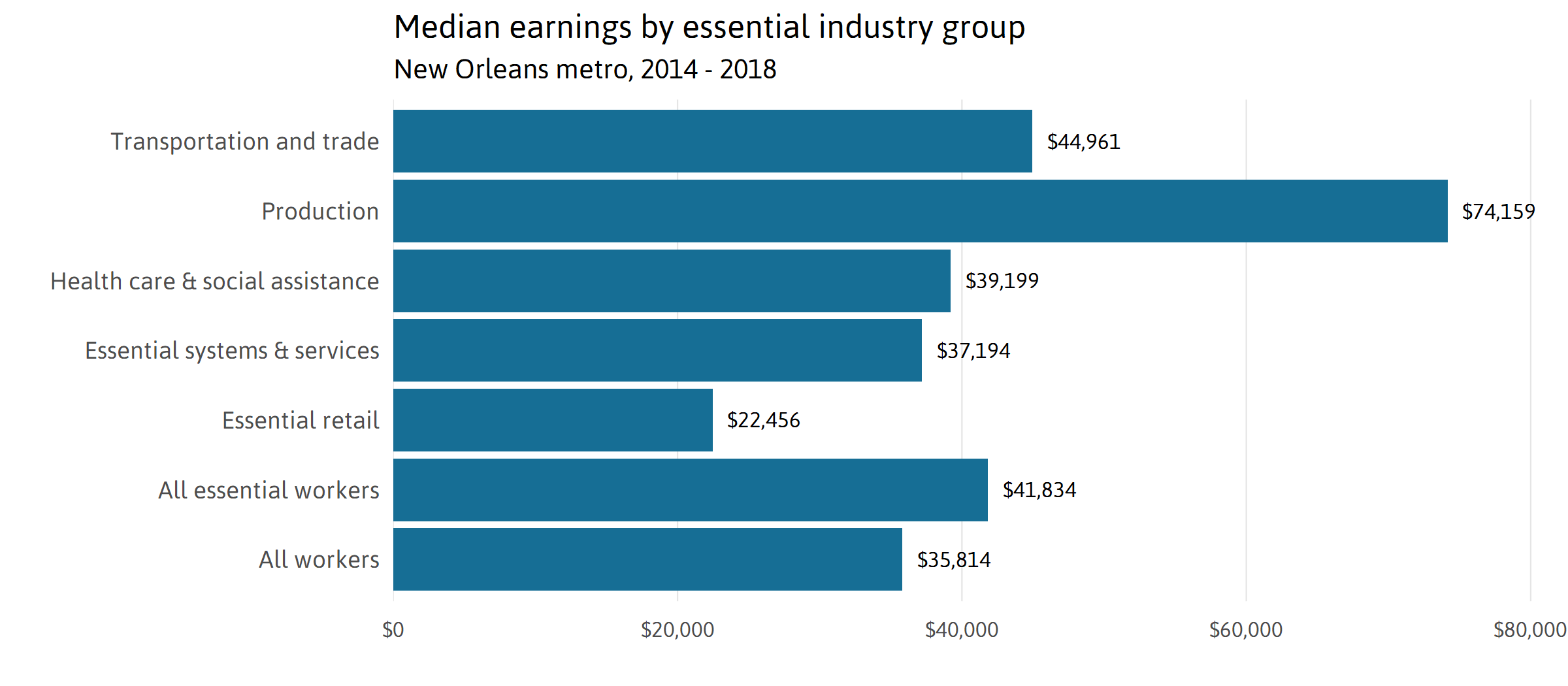

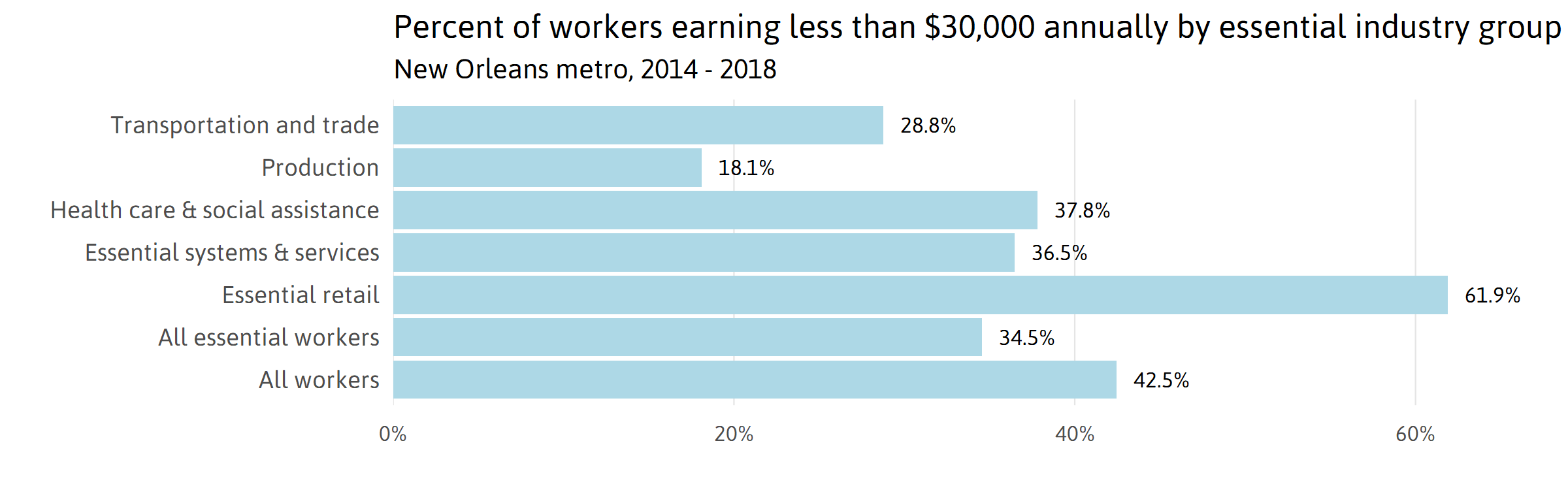

Essential workers have slightly higher median earnings than workers in the metro overall. Yet, earnings vary substantially across types of essential work. While essential production workers have high median earnings, essential retail workers have much lower median earnings. Almost 62 percent of essential retail workers make less than $30,000 (comparable to the annual earnings of a full-time worker earning a $15 hourly wage), as do

38 percent of health care and social assistance workers. These are two groups of workers putting themselves at high risk, and many for low pay.

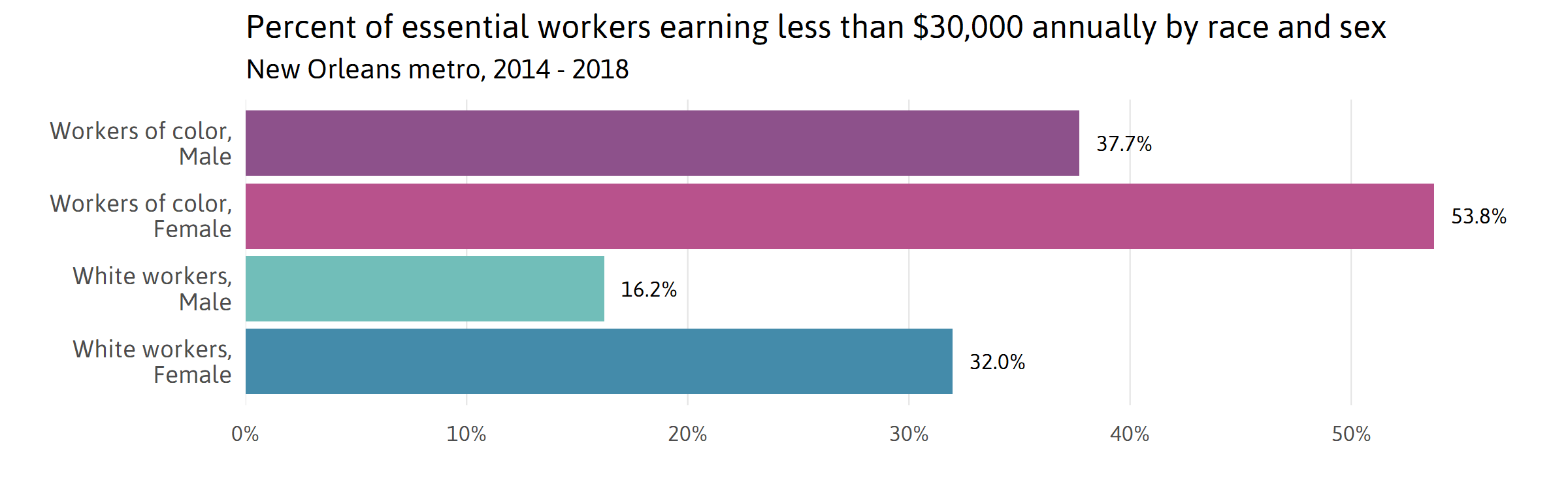

Broken out by race and gender, 38 percent of men of color who are essential workers make less than $30,000 compared with 16 percent of white men who are essential workers. And

54 percent of women of color who are essential workers make less than $30,000 compared with 32 percent of white women who are essential workers. Women of color who are essential workers are more likely to make less than $30,000 than the metro workforce overall.ix Women of color make up 24 percent of the total workforce but 41 percent of the low-wage essential workforce.

Age and family responsibilities

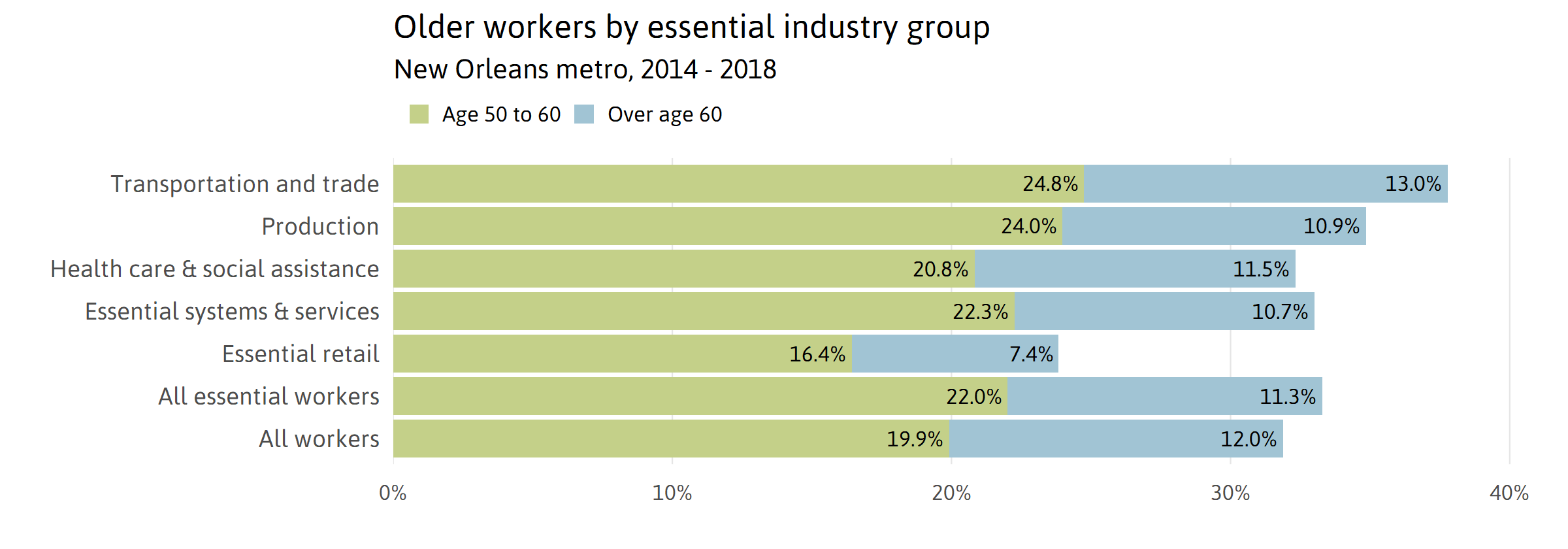

Essential workers tend to be slightly older than the workforce overall. The median age of essential workers is 42, compared with 40 for all workers. 33 percent of essential workers are over age 50,x and 11 percent of essential workers are in the especially vulnerable age group over 60. Essential retail skews younger, though almost one quarter of essential retail workers are still over 50. Transportation and trade has the largest share of workers vulnerable because of their age—38 percent over 50 and 13 percent over 60.

Family responsibilities may present additional challenges for essential workers. In the New Orleans metro, 33 percent of essential workers have children under 18 compared with 28 percent of all workers. In terms of childcare needs, 20 percent of essential workers have children under 10, as they continue to work outside the home while schools are closed. In addition, 18 percent of essential workers in the metro live with someone over the age of 60. Aside from regular care responsibilities, this presents a risk for infection and serious illness from COVID-19 for these older residents whose family or household members are essential workers. Access to paid leave and childcare may be especially critical issues for essential workers.

Access to affordable housing, food, and health insurance

Taken as a whole, essential jobs are not necessarily paid less than other workers. Yet, their access to affordable housing, food, and health insurance offers a window into broader patterns of vulnerability for workers in the New Orleans metro.

- 38 percent of essential workers who rent spend at least 30 percent of their household income on rent and utilities (or are “rent burdened”), roughly the same rate as all workers who rent.xiv

- In the previous year, 10 percent of both groups of workers had used SNAP benefits.

- 10 percent of essential workers reported they did not have health insurance coverage. At 15 percent reporting no coverage, essential retail workers were more likely to lack health insurance than other essential workers.xv

Essential workers’ access to health insurance, food, and affordable housing also varies by race and gender.

- While 6 percent of essential workers who are white reported they did not have health insurance, 14 percent of essential workers of color were not covered.

- While 22 percent of all employed men of color reported not having health insurance, only 16 percent of those in the essential workforce were not covered.

- Relative to other essential workers, women of color face constraints accessing affordable housing and food. Among essential workers who rent, half of those who are women of color live in rent burdened households. In the previous year, 1 in 5 women of color in essential jobs had used SNAP.

Conclusion

Our profile of essential workers only points to some of the areas where job quality, worker demographics, and pandemic health risks may overlap. These considerations are especially urgent as essential workers put themselves at potentially greater risk to maintain their jobs and essential functions for the community at large. Understanding who could be put at risk from going to work will continue to be important as policymakers and businesses plan to resume “non-essential” functions in a responsible manner.

We have already learned that COVID-19 is not affecting the population equally.xvi The CDCxvii, experts at Brookingsxviii, and othersxix have identified the overrepresentation of black workers in the essential workforce as one potential factor driving the racial disparities in COVID-19 related deaths. Our estimates suggest that workers of color are overrepresented in the lower-wage essential workforce and in certain high-contact essential industries like health care, retail, and transportation and trade. Many of these essential workers also struggle with access to affordable housing, food, and health insurance.

These overlapping vulnerabilities and differential risks related to essential work and working conditions are only some of the many factorsxx to investigate further as data collection and research on race and COVID-19 continues. In the meantime, meeting the needs of essential workers, not just temporarily while initial plans for reopening go into effect, but over the long term as businesses try to recover, will remain central to managing the region’s economy and the health and well-being of its workers.

Methodology

Our profile of essential workers draws from two national analyses with different approaches to defining essential industries.xxi The Center for Economic and Policy Researchxxii highlighted low-wage work in a small set of frontline industries: grocery, pharmacy, transit, delivery and logistics, cleaning, health care and social assistance. A separate analysis from Brookingsxxiii drew from a broader list of “essential critical infrastructure workers” published by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. To paint a comprehensive picture, we started by combining these two lists of industries, reviewed every industry available in the American Community Survey (ACS), and made minor modifications to better reflect the regional economy. Our final list includes 74 ACS industries as essential. The ACS industries and their grouping into categories are available in this spreadsheet.

Like the CEPR study, The Data Center used a five-year sample of ACS microdata, 2014-2018, to develop the estimates. This data was sourced from IPUMS-USA. All data is reported for the 8-parish metro area and includes workers who reported that they worked the previous week and worked for wages and salaries (i.e., self-employed workers are excluded). Earnings and household income are adjusted to 2018 dollars using the CPI-U based on the guidance on the IPUMS-USA website.xxiv

Sources and Footnotes

i Rho, H., Brown, H. and Fremstad, S. (2020). “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries.” Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/a-basic-demographic-profile-of-workers-in-frontline-industries/

ii Tomer, A. and Kane, J. (2020). “How to protect essential workers during COVID-19.” Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/how-to-protect-essential-workers-during-covid-19/

iii Rho, H., Brown, H. and Fremstad, S. (2020). “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries.” Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/a-basic-demographic-profile-of-workers-in-frontline-industries/

iv Office of the New York City Comptroller, Bureau of Policy & Research (2020). “New York City’s Frontline Workers.” https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/new-york-citys-frontline-workers/

v Schuster, L. and Mattos, T. (2020). “A Profile of Frontline Workers in Massachusetts.” Boston Indicators. https://www.bostonindicators.org/article-pages/2020/april/frontline_workers

vi Mendes, K. and Goren, L. (2020). “Profile of Essential Workers in Virginia During COVID-19.” The Commonwealth Institute. https://www.thecommonwealthinstitute.org/2020/04/22/profile-of-essential-workers-in-virginia-during-covid-19-women-people-of-color-and-immigrants-are-important-contributors-in-front-line-virginia-industries/

vii Robertson, C. and Gebeloff, R. (2020) “How Millions of Women Became the Most Essential Workers in America.” Nytimes.com https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/18/us/coronavirus-women-essential-workers.html

viii Workers of color encompasses all race categories in IPUMS except white and includes the ethnicity of Hispanic or Latino. Within the New Orleans metro’s essential workforce of color, 76 percent are black and 14 percent are Latinx. Black workers represent 36 percent of all essential workers, while Latinx workers are 7 percent of the essential workforce.

ix This pattern holds across the different groups of essential industries.

x This is consistent with national data for frontline workers and all workers. See Rho, H., Brown, H. and Fremstad, S. (2020). “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries.” Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/a-basic-demographic-profile-of-workers-in-frontline-industries/

xi Child Day Care Services are not included in other estimates of essential workers in this analysis.

xii As of May 6, 2020, 60 childcare centers in the 8-parish metro region were open and enrolling. Agenda for Children. http://www.agendaforchildren.org/covid-19-child-care-for-essential-workers.html

xiii Vogtman, J. (2017). ”Undervalued: A Brief History of Women’s Care Work and Child Care Policy in the United States.” National Women’s Law Center. https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/final_nwlc_Undervalued2017.pdf

xiv Here, rent burden is defined as living in a renting household where more than 30 percent of income is spent on rent.

xv Louisiana implemented Medicaid expansion in 2016. This analysis uses a sample that combines five years from 2014 to 2018. As a result, the current rate of uninsured workers is likely slightly lower than estimates presented here.

xvi “COVID-19 Racial Disparities in U.S. Counties.” Retrieved from https://ehe.amfar.org/inequity?_ga=2.208401682.1037173503.1588730379-222819240.1588730379

xvii COVID-19 in Ethnic and Racial Minority Groups. Retrieved from the CDC on May 5, 2020: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html

xviii Ray, R. (2020) ”Why are blacks dying at higher rates from COVID-19?” Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/04/09/why-are-blacks-dying-at-higher-rates-from-covid-19/

xix ACLU Massachusetts. (2020). “Data show COVID-19 is hitting essential workers and people of color hardest.” https://www.aclum.org/en/publications/data-show-covid-19-hitting-essential-workers-and-people-color-hardest

xx In addition to higher representation in the low-wage essential workforce, other structural conditions that may be related to racial disparities in COVID-19 deaths include, but are not limited to, inequities in neighborhood funding and resources, long-term exposure to pollutants, and interactions with and access to institutions such as those of health care and criminal justice.

Ray, R. (2020). “How to reduce the racial gap in COVID-19 deaths.” Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/04/10/how-to-reduce-the-racial-gap-in-covid-19-deaths/

xxi Other similarly themed studies have used occupation rather than industry to identify health risks to workers.

xxii Rho, H., Brown, H. and Fremstad, S. (2020). “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries.” The Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/a-basic-demographic-profile-of-workers-in-frontline-industries/

xxiii Tomer, A. and Kane, J. (2020). “How to protect essential workers during COVID-19.” Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/how-to-protect-essential-workers-during-covid-19/