The New Orleans Index at Twenty: Measuring Greater New Orleans’ progress toward resilience

Published: Aug 05, 2025

Executive Summary

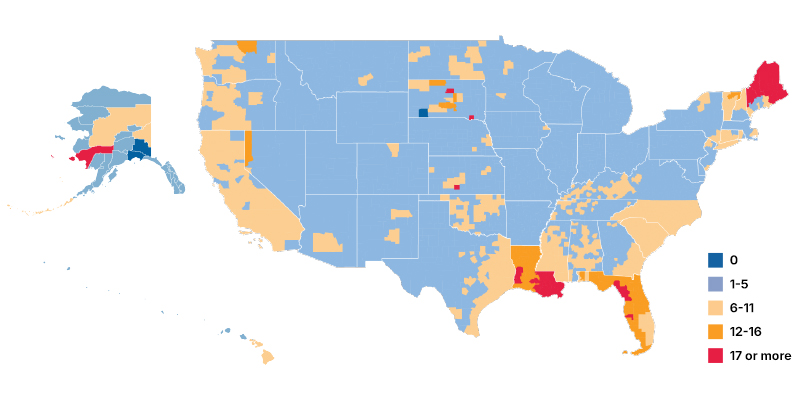

Two decades ago, when Hurricane Katrina struck and the federal levees protecting Metro New Orleans failed, the U.S. experienced a disaster on an unprecedented scale. Extreme weather like Hurricane Katrina, has become more common since, and Americans can now expect to witness multiple large-scale shocks annually. Since 2020 for example, Metro New Orleans itself has been hit by Hurricanes Zeta, Ida, and Francine in quick succession. The summer of 2023 brought a record number of days exceeding 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and extreme rainfall events and tornadoes are increasing in frequency. Other types of shocks are also a threat. Between March 2020 and March 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic killed more than 2,300 people across Metro New Orleans.2 All total, each parish in Metro New Orleans has had at least 17 declared disasters since 2020—four times more than the national average—making Metro New Orleans a national outlier.

Number of FEMA disaster declarations by county

Cumulative January 2020 through December 2024

Source: FEMA. See source notes on page 46 for technical details.

August 29, 2025 is the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, and an important moment to reflect on the metro’s progress since that historic event. Given the increasing number of shocks the region is experiencing, arguably the most important assessment is of the region’s resilience capacity. To be sure, the metro has engaged in a myriad number of actions to reduce its flood risk and restore its housing stock. But resilience requires more than strong infrastructure and housing.

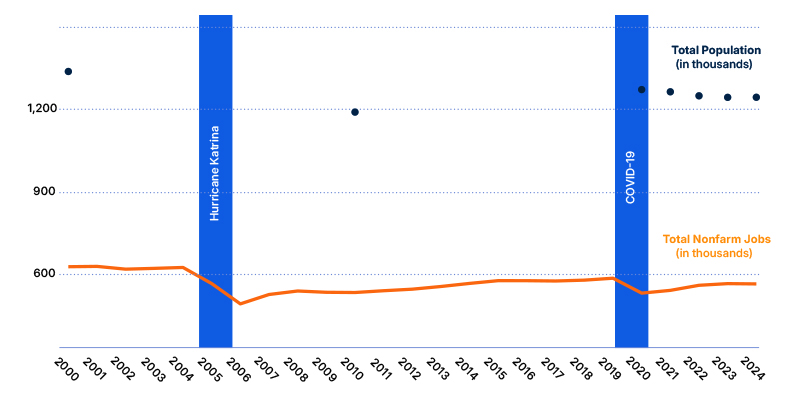

Regional resilience has two closely related dimensions. First, resilience describes a region’s actual performance following a disruption. A metro area is considered resilient if it returns to, or exceeds, its pre-shock trajectory.3 Looking at the key metrics of jobs and population, we see Hurricane Katrina and the COVID-19 pandemic were significant blows to Metro New Orleans’ economy, which now has 10 percent fewer jobs and 7 percent smaller population than in 2000—suggesting significant weaknesses in the region’s ability to rebound to pre-disaster trend lines.

Metro New Orleans Jobs and Population

Annual averages

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Decennial 2000, 2010, and 2020, Population Estimates 2021-2024, and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. See source notes on page 46 for technical details and a graph of job change for the 50 largest metropolitan areas from 2000 to 2024.

Second, resilience refers to the capacities, resources, and traits—whether inherent or developed—that enable a metropolitan area to absorb, adapt to, or recover from a shock. That’s an important point; a resilient metro area is one that isn’t just trapped in a cycle of disaster response and recovery, but is also able to adapt in ways that reduce the risks to shocks communities and the region face. A review of academic literature and case studies reveals a shared hypothesis regarding the factors that strengthen a region’s ability to rebound from, adapt to, or mitigate adverse shocks. These factors include:

- A strong and diverse regional economy: Economic diversity, particularly across major traded industry clusters, enhances a region’s ability to withstand or avoid economic disruptions. Robust entrepreneurship contributes to economic diversity by introducing new businesses that can broaden the industrial base of a metro.

- A highly skilled and educated workforce: Workers with advanced skills and formal education are more adaptable to evolving economic demands. Regions with a high concentration of well-educated residents are better positioned to manage and recover from economic shocks.

- Access to wealth: The availability of financial capital—across government, private, philanthropic, and individual sources—provides a buffer during crises and enables investment in recovery, reconstruction, and reform.

- Robust social capital: Communities characterized by strong place attachment, wellness, civic engagement, and social cohesion tend to be more resilient. A narrower gap between high- and low-income residents also contributes to social cohesion and, therefore, resilience capacity.

- Community competence: The capacity of a community to address challenges, generate innovative solutions, implement responsive policies, and build effective political and institutional partnerships is critical for adaptive and sustained recovery.

Together, these attributes form the foundation for regional resilience and influence how effectively a metro area can navigate and recover from a range of shocks. The New Orleans Index at Twenty examines more than 20 indicators to provide essential insights into the region’s resilience capacity, highlighting strengths and weaknesses across key contributing factors organized into four categories of housing and infrastructure, economy and workforce, wealth, and people. The Index serves as a valuable tool for guiding efforts to boost the resilience capacity of Metro New Orleans. Key findings include:

Housing and infrastructure

Metro New Orleans will need substantial new investments in stronger housing stock, flood protection, and reliable electric supplies in order to withstand the shocks to come.

-

Roughly 4,000 Metro New Orleans homes have now upgraded their roofs to the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety’s new FORTIFIED roof standard. But this leaves some 99 percent of homes without FORTIFIED roofs and vulnerable

to frequent storm-force winds. - A full 85 percent of properties in Metro New Orleans have a major or greater risk of experiencing some level of flooding in the next 30 years.

- Over the last decade, Louisiana has experienced the most cumulative power outage hours (198) of any state in the nation.

Economy and workforce

Legacy industries like tourism, oil & gas, shipping, and petrochemical manufacturing still

dominate the New Orleans economy, but environmental services, water management, video production, and performing arts are contributing to diversification of the metro economy. Entrepreneurship surged post-Katrina and remains high 20 years later. Adult educational attainment levels and internet access rates have caught up to the nation but remain below that of other large metros

- Despite substantial private and public investments, tourism, oil & gas, water transportation, and upstream chemical clusters have shed 38 percent of jobs since 2004 primarily due to increasing replacement of workers with automation and improved technology that increase efficiency.4

- Since 2004, New Orleans’ environmental services cluster has more than doubled. But construction products and services—linked to water management—have declined since 2018.

- Performing arts and video production jobs in Metro New Orleans have grown since 2004 but still offer low average wages—$43,603 and $41,950—despite strong national compensation of $77,903 and $114,960 respectively.

-

Post-Katrina, Metro New Orleans has consistently outperformed both the nation and other large metros in business startup rates. During the 3-year period from 2023 to 2025, 592 out of every 100,000 adults in the region launched new businesses

annually—34 percent above the national rate and 29 percent above the average of the other 49 largest U.S. metros. - Educational attainment in Metro New Orleans has risen to match the national average, with 35 percent of adults holding a bachelor’s degree and 63 percent having some college education. However, the region still trails the other 49 largest metros, where 40 percent hold a bachelor’s degree and 67 percent have some college, as of 2023.

- The share of Metro New Orleans households without internet declined to 6.4 percent in 2023, but remains above the 4.1 percent average among the 50 largest metros.

Wealth

Wealth is a protective buffer when disasters strike. It can be used to support preparedness and also contribute to a nimble recovery, reducing the likelihood that a shock will push a family into chronic poverty. But (material) wealth is in short supply in New Orleans, with below average philanthropic resources, and high poverty levels. Among those New Orleanians with positive net assets, racial gaps are significant, but so are gaps within races. To the extent that wealth is held in homeownership, these assets may be insecure as homeowners are increasingly dropping insurance coverage.

- In Metro New Orleans, White households hold about 10 times the median wealth of Black households and more than six times that of Hispanic households. These gaps persist even after factoring in education and age.

- Although 85 percent of properties face a major or higher risk of flooding, flood insurance coverage varies widely across Metro New Orleans. About half of all properties in St. Tammany, Jefferson, Orleans, and St. Bernard parishes are insured. And only one-third are covered in St. Charles and Plaquemines. In St. John the Baptist, just 25 percent of properties have flood insurance.

- The poverty rate in Metro New Orleans, at 20 percent, is significantly higher than the national rate of 12 percent. But the majority of people in poverty (130,000) live in the parishes surrounding New Orleans rather than in the city itself.

- Per capita philanthropic spending by Metro New Orleans foundations is roughly half the national average, and ranks 41st out of the 50 largest metros.

People

Metro New Orleans’ people are its strength. While rising income inequality and a sharp decline in union membership have weakened social cohesion, the region’s rich tradition of social clubs continues to foster community connection, and attachment to place remains strong with 71 percent native to Louisiana.

- Metro New Orleans has enjoyed a high nativity rate for decades. With 71 percent of residents native to Louisiana, New Orleanians’ attachment to place greatly exceeds the national average and that of other large metros.

- Income inequality undermines social cohesion, and in Metro New Orleans, the top 5 percent of households earn 12 times more than the bottom 20 percent, surpassing the national income ratio of 10 to 1.

- The number of workers covered by union membership has fallen in Metro New Orleans by more than half over the last 24 years.

- New Orleans has a long tradition of social aid and pleasure clubs historically rooted in Black communities to address unmet needs and support cultural and justice movements. With 172 social, pleasure or recreational clubs, New Orleans is near the top in social clubs per capita among the 50 largest metros.

- In Metro New Orleans, more than 200,000 residents are over 65 years old and are increasingly likely to need assistance responding to and recovering from disasters.

- The share of working age adults without health insurance has dropped from 24 percent in 2013 to 10 percent in 2023 in Metro New Orleans, bringing it in line with the national average and the other 49 largest metros.

Conclusion

Researchers examining disasters over the past century have found that large-scale catastrophes like Hurricane Katrina often reinforce existing trends and deepen inequalities. However, some regions have managed to break from these patterns by using recovery aid to reform and strengthen institutions that reduce inequality and improve social cohesion, while also tapping into new and emerging industries to diversify and bolster their economies.5

The papers accompanying The New Orleans Index at Twenty cover reform efforts across a range of domains including water policy, community safety, K-12 education, land use planning, and climate adaptation. They reveal that Metro New Orleans has made good progress toward increasing resiliency through a large number of key institutional and sector wide reforms. There is no doubt that external philanthropy, working with local philanthropy, played a major role in these gains.6

To date, economic transformation remains a work in progress. Entrepreneurship is a bright spot, and if well-fortified and directed, can help the economy to diversify and weather the shocks ahead. Recent investments in lower-carbon energy production will help nudge the economy toward an internationally growing market. Recently passed increases in oil & gas revenue sharing which, by Louisiana law, must go to coastal restoration, can refortify a growing industry specialization.7 Ensuring this work sustainably grows the economy will require the deliberate reinforcement of the core dynamics of cluster development: the sharing of inputs and resources, the alignment of workers and firms with high-productivity roles, and the exchange of specialized knowledge that drives innovation.8 Implementing the 50-year, $50 billion Coastal Master Plan remains an important component of both shoring up flood protections and supporting growth in this industry.

At the end of the day, New Orleanians and all Americans must plan for a future with increasingly frequent extreme weather events. Compounding this challenge will be the tremendously disruptive changes that AI will bring to the metro and national economy. There is no doubt that the next 20 years will include a number of shocks for New Orleans and the entire country. New Orleanians have demonstrated their capacity for community problem solving by substantially reforming a number of key institutions. And New Orleanians’ love of their home contributes to a culture of care that is exemplary. As together we navigate the challenges the future will bring, leaders and residents must unite around policies that have as their primary goal a high quality of life for everyone.

Continue reading the full report [Download PDF]

Endnotes

1 The Data Center. “What Is a Metropolitan Statistical Area? | The Data Center,” September 19, 2024. https://www.datacenterresearch.org/reports_analysis/what-is-a-metropolitan-statistical-area/

2 The Data Center, “Monitoring the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic in New Orleans and Louisiana | The Data Center,” March 7, 2024, https://www.datacenterresearch.org/covid-19-data-and-information/covid-19-data/

3 Hill, Edward, Travis St Clair, Howard Wial, Harold Wolman, Patricia Atkins, Pamela Blumenthal, Sarah Ficenec, and Alec Friedhoff. 2012. “Economic Shocks and Regional Economic Resilience.” Urban and Regional Policy and Its Effects: Building Resilient Regions, 193–274. https://nyuscholars.nyu.edu/en/publications/economic-shocks-and-regional-economic-resilience.; Regional Resilience: How Do We Know It When We See It? Kathryn A. Foster Director, University at Buffalo Regional Institute (SUNY) Member, Building Resilient Regions Research Network Presentation to the Conference on Urban and Regional Policy and Its Effects.

4 Dismukes, David E. Unconventional Resources and Louisiana’s Manufacturing Development Renaissance. Louisiana State University, 2013. https://www.lsu.edu/ces/publications/2013/ANGA_Report_11Jan2013.pdf.; Hobor, George, and Elaine Ortiz. The Transformative Possibility of the New “Energy Boom” in Southeast Louisiana. The Data Center, 2014. https://gnocdc.s3.amazonaws.com/reports/GNOCDC_NewEnergyBoominSoutheastLouisiana.pdf.

5 R.W. Kates et al., “Reconstruction of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: A Research Perspective,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103 (40) (2006): 14653-14660.

6 See forthcoming paper by Halima Leak Franics in The New Orleans Index at Twenty Collection.

7 Guilbeau, Julia. “How Will the ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ Change Louisiana? What It Means for Tax Cuts, Medicaid, More.” The Times Picayune, July 8, 2025. https://www.nola.com/news/politics/big-beautiful-bill-louisianamedicaid-snap/article_c8efe3e9-ee9e-4c75-9386-beab3579a67c.html

8 The Data Center. “Changing Coast, Evolving Coastal Economy: The Water Management Cluster in Southeast Louisiana in Retrospect and Prospect.” Accessed July 31, 2025. https://www.datacenterresearch.org/reports_analysis/changing-coast-evolving-coastal-economy-the-water-management-cluster-insoutheast-louisiana-in-retrospect-and-prospect/